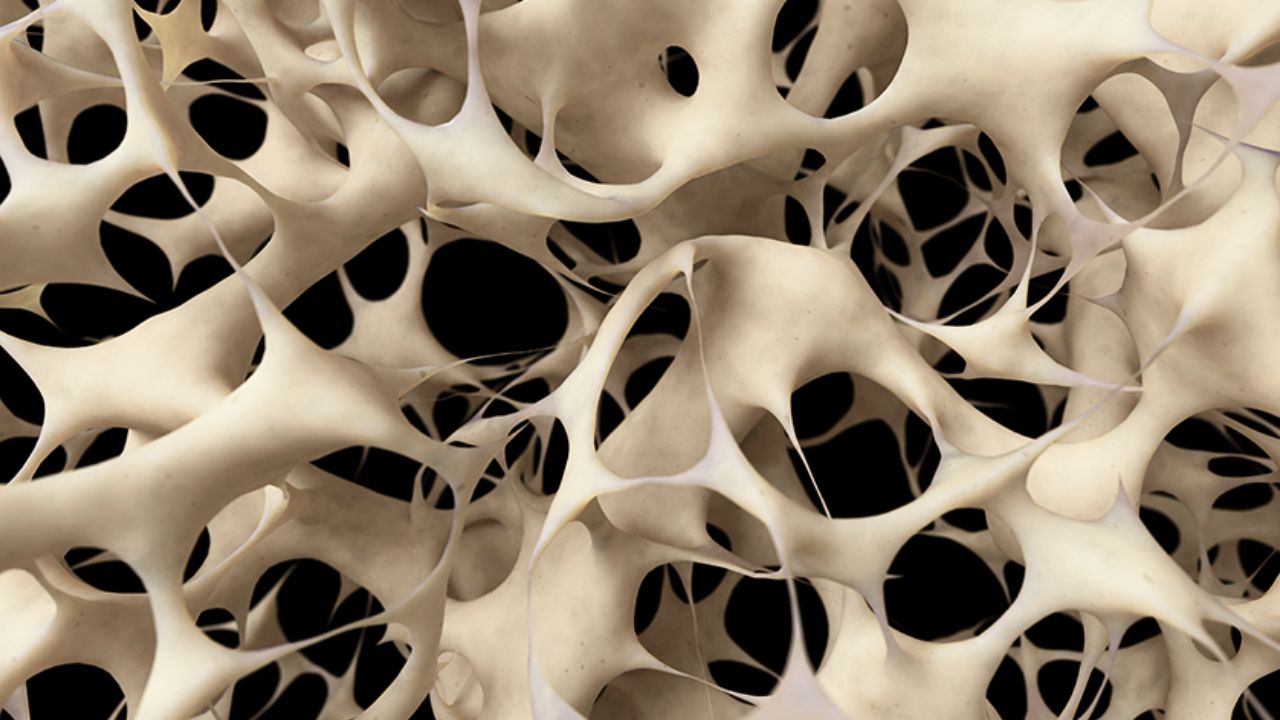

A breakthrough in bone biology may open the door to new treatments for osteoporosis, a disease that weakens bones and affects millions worldwide. Researchers in Germany and China have zeroed in on a protein receptor that could be the body’s own “switch” for strengthening bone.

A Hidden Lever for Bone Density

The international study, led by the University of Leipzig and Shandong University, identified the receptor GPR133 (ADGRD1) as a key driver of bone strength. This receptor sits on osteoblasts — the bone-building cells responsible for creating new bone tissue.

Earlier genetic studies had hinted at a link between variations in the GPR133 gene and bone density. To test its function directly, researchers turned to mouse models.

- Mice bred without the gene developed fragile bones, mimicking human osteoporosis.

- When the receptor was activated by a compound called AP503, bone production surged, and bone strength significantly improved.

“Using AP503, which was only recently identified via a computer-assisted screen as a stimulator of GPR133, we were able to significantly increase bone strength in both healthy and osteoporotic mice,” explained Ines Liebscher, a biochemist at Leipzig.

Exercise + Biology = Stronger Bones

The study also revealed that stimulating GPR133 worked even better when paired with exercise. This suggests future therapies could not only rebuild fragile bone but also enhance the natural strengthening effect of physical activity.

“If this receptor is impaired by genetic changes, mice show signs of loss of bone density at an early age – similar to osteoporosis in humans,” Liebscher added.

Implications for Osteoporosis Treatment

Osteoporosis currently has no cure. Existing treatments — from bisphosphonates to hormone therapies — can slow bone loss but often come with side effects and diminishing results over time.

By contrast, targeting GPR133 may allow scientists to:

- Boost bone formation in healthy individuals, potentially preventing osteoporosis.

- Restore degraded bone in older patients, especially women after menopause.

“The newly demonstrated parallel strengthening of bone once again highlights the great potential this receptor holds for medical applications in an aging population,” said Juliane Lehmann, a molecular biologist at Leipzig.

Looking Ahead

While the findings are based on animal studies, the mechanisms are likely similar in humans. The next step will be testing whether AP503 or similar compounds can safely stimulate bone growth in people.

If successful, the discovery of GPR133 could mark a paradigm shift in bone health — moving from managing decline to actively rebuilding strength.

FAQs:

1. What is osteoporosis?

It’s a disease where bones become thin and brittle, increasing the risk of fractures. It often affects postmenopausal women but can impact men too.

2. What makes GPR133 important?

It’s a receptor on osteoblasts that helps regulate bone formation. Without it, bones weaken significantly.

3. What is AP503?

A newly discovered compound that activates GPR133, triggering osteoblasts to build stronger bone.